Costa Rica “La Lapa” (SHB)

About Costa Rica and its Coffee Production

Costa Rica’s history is inextricably linked to coffee production: in fact, on the eve of the country’s independence from Spain, in 1821, free coffee seeds were distributed by the local government as a means of promoting coffee production to bolster the economy. Since it was first shipped to England in 1843, coffee has been one of Costa Rica’s key exports (it was, in fact, the ONLY export until 1890) and is linked to Costa Rica’s identity in a way that no other agricultural product is. The country’s producers were also some of the first ‘responders’ in the global movement towards quality in the cup; nonetheless, as recently as the 1980s, speciality coffee was barely understood, and Costa Rica’s production was largely lumped together as undifferentiated SHB and HB.

Today, Costa Rica has answered the calls of export buyers for greater traceability and remains a leader in the boutique ‘micro mill’ and micro-lot movements, which allow specific lots to be traced back to a unique farm or plot. In many ways, Costa Rica is an ideal contributor to the movement: the many and varied microclimates found throughout the coffee-producing regions in this small nation provide a wealth of distinctive flavour characteristics determined by coffee varieties, latitude, altitude, soil type, rainfall and variation in temperature. Furthermore, 90 per cent of the country’s 50,000 coffee farmers work on small farms of less than five hectares, which ensures small lot sizes by default.

The majority of farmers in Costa Rica do not have facilities to process their own coffee but rather pick their cherries during the day and deliver them to a private- or cooperative- owned mill in their region in the afternoon. In the past, these mills produced predictable, clean washed coffees – though not so much interesting or distinct. Then, in the mid-noughts, a small revolution took place with regards to processing and approaches to milling.

Where does the Costa Rica “La Lapa” (SHB) come from?

The northern region of Costa Rica’s Central Valley produces coffees that are mild, sweet, and bright. This region produces the magnificent La Lapa bean at approximately 1500 metres above sea level. This rich, fertile soil produces a bean with a mild to round flavour, making it an excellent blended bean. La Lapa is a full-bodied coffee producing a slightly delicate, fruity finish.

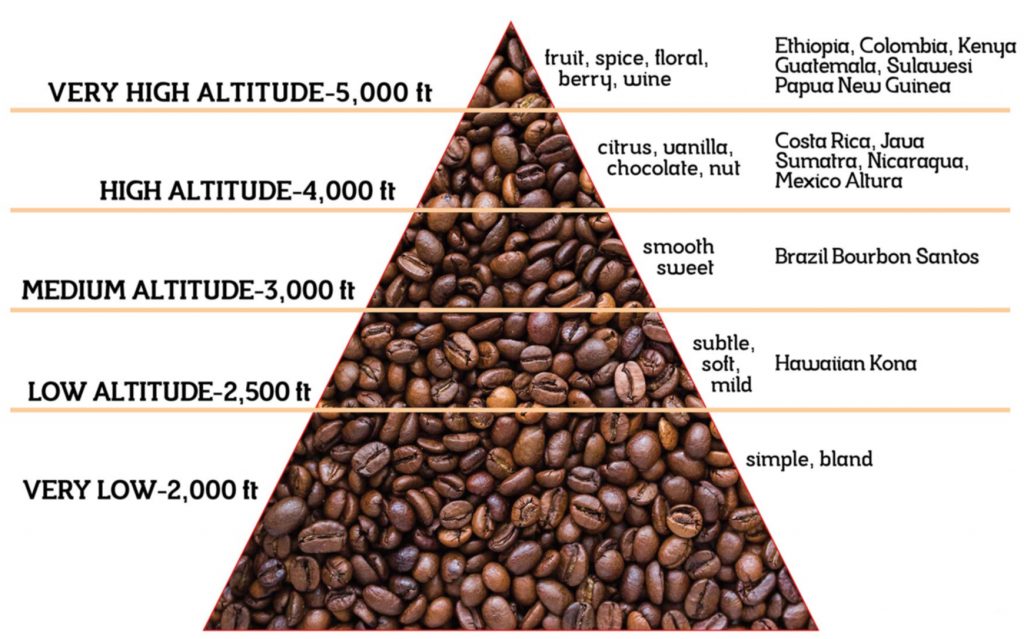

Costa Rica has one of the widest ranges of microclimates, due to the drastic change in altitude and climate over relatively short distances. These differences in climatic factors determine the flavour of the final cup. Costa Rican coffee has set the standards for fine wet-processed coffee for the rest of Central and South America.

Coffee is grown in Costa Rica on both the Atlantic and Pacific slopes at altitudes between 1600 and 5400 feet. The highest grade is called Strictly Hard Bean, grown at elevations over 3900 feet. These altitudes produce the best conditions for bean growing and in turn, Costa Rica produces some exceptional coffees, renowned for their brilliance, balance and complexity.

Costa Rica is the only country where only the Arabica varieties, by law, may be grown.

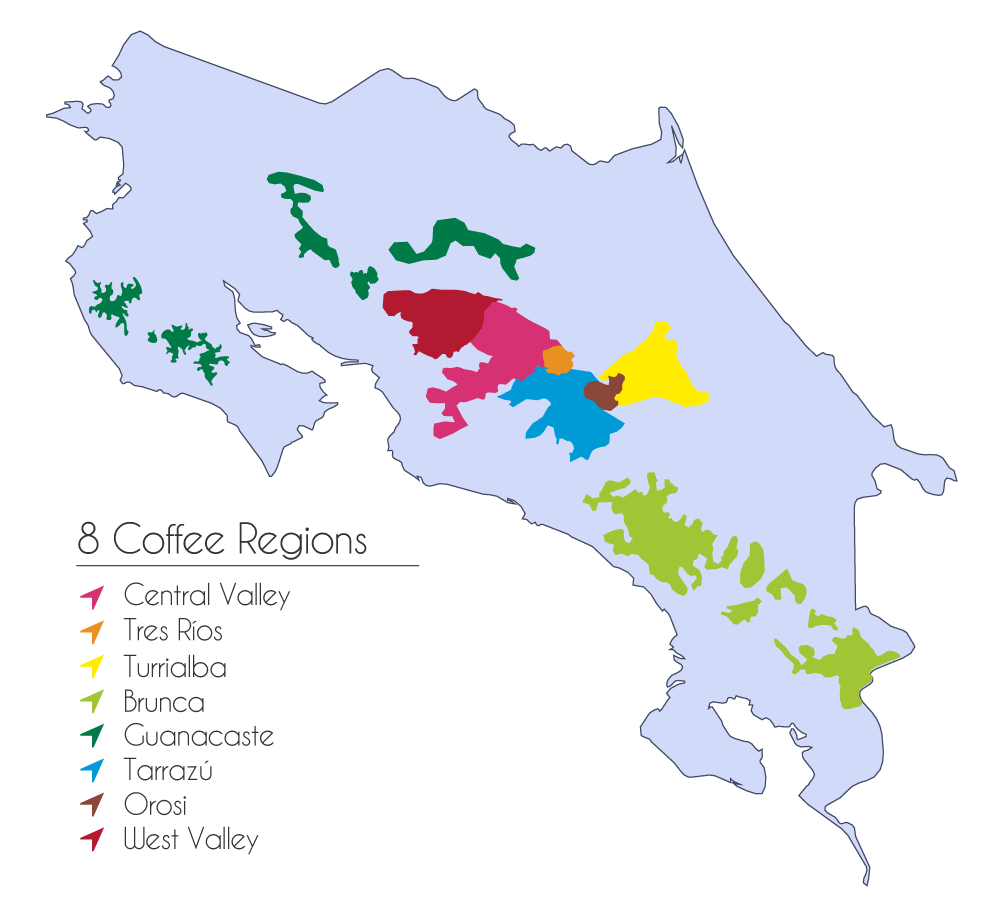

Our La Lapa variety comes from the following regions of Costa Rica; Central and West Valley

Central Valley (approx. 15% of production) Altitude: 1,000 to1,200 metres above sea level

Surrounded by San Jose, Heredia and Alajuela, the Central Valley has well defined rainy and dry seasons. The area produces a balanced cup with hints of chocolate and fruit flavors and the subtle smell of honey.

Under the influence of the Pacific watershed, the privileged Central valley enjoys a well-defined wet and dry season and reasonable altitudes.

This region’s soil has a slight tropical acidity, a result of its enrichment by volcanic ashes. An abundance of organic materials favours adequate root distribution, soil humidity and good oxygenation.

The coffee plantations here are some of the oldest in Costa Rica but are also fast disappearing due to the pressure of population and industrial development. Some Bourbon varietal is still cultivated in the Central Valley.

West Valley (approx. 25% of production)

Altitude: 1,200 to 1,700 metres above sea level

The West Valley’s first inhabitants brought coffee from the Central Valley, igniting progress in the region. Around 85% of coffee growers here harvest from 1 to 100 quintals (a quintal is equal to 46 kilograms) annually, and the region’s average production falls between 307,000 and 460,000 60kg bags of Hard Bean, Good Hard Bean and Strictly Hard Bean (HB, GHB, SHB).

The predominant varieties grown in the region are Caturra and Catuaí, established across an area of approximately 22,000 hectares; in some cases, remnants of the Villa Sarchí and Villalobos varieties can be found here.

The West Valley is one of the most complex regions in the production of high-quality coffee, thanks to its microclimates and the possibility of collecting the ripe cherry during the drier, summer months, and produces some of Costa Rica’s finest coffees. Coffees from this area have featured highly amongst the winners in the Cup of Excellence auctions due, also, to the excellent work of the many micro mills. This has enabled these prized cup profiles to be maintained and further enhanced.

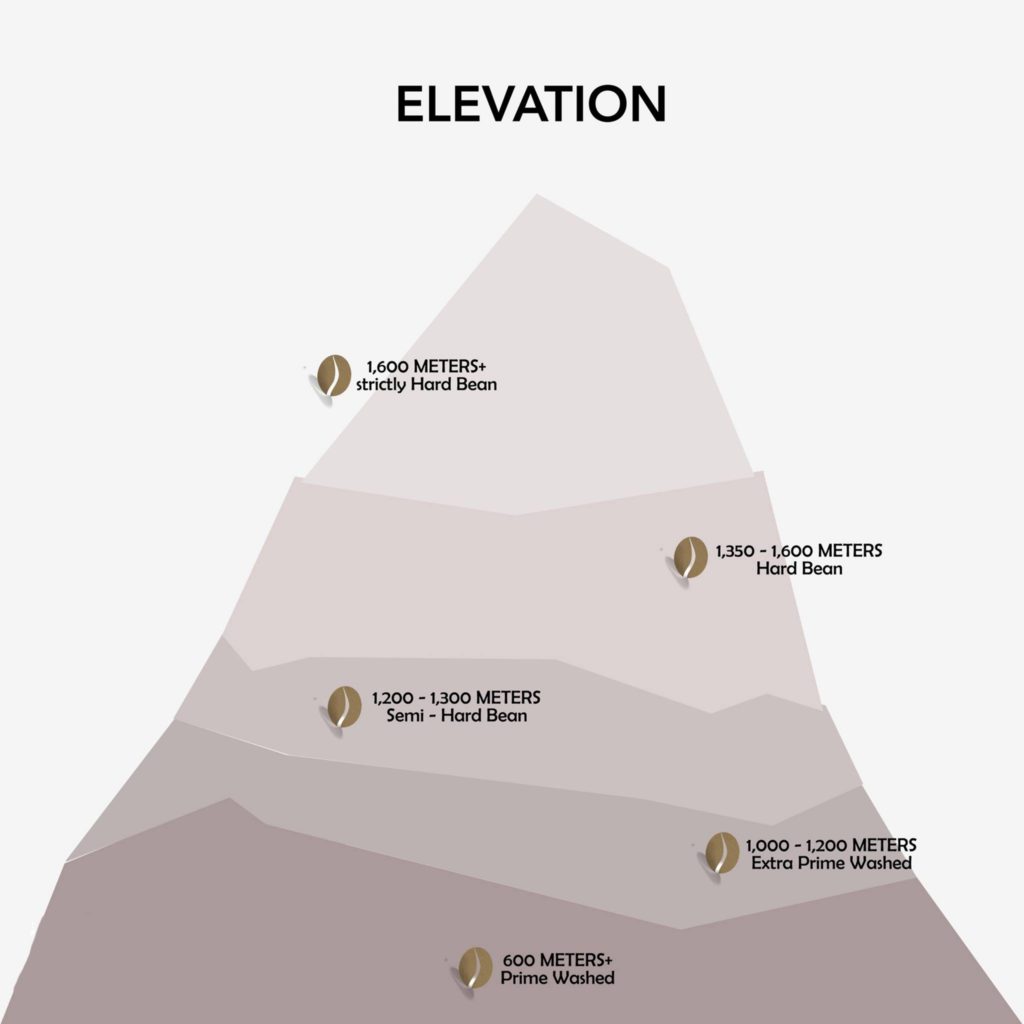

What does SHG, SHB, GHB, HG & HB mean?

Costa Rican coffee beans are graded using an attitude-based system that grades by hardness.

Strictly Hard Bean

Synonymous with “strictly high grown (SHG)”, “strictly hard bean (SHB)” usually refers to coffee grown at altitudes higher than about 4,500 feet above sea level. Beans grown at high altitudes mature more slowly and grow to be harder and denser than beans grown at lower elevations. The inherent consistency and taste attributes of high grown beans make them more desirable, and generally more expensive than coffees grown at lower elevations.

Hard Bean

Synonymous with “high grown (HG)”, “hard bean (HB)” refers to coffee grown at altitudes about 4,000 – 4,500 feet above sea level. Beans grown at high altitudes mature more slowly and grow to be harder and denser than beans grown at lower elevations. The inherent consistency and taste attributes of high grown beans make them more desirable, and generally more expensive than coffees grown at lower elevations.

Good Hard Bean (GHB)

A grade of coffee grown at altitudes above 3000 feet. The term varies depending on the country where the bean is grown.

Medium Hard Beans (MHB)

including beans from elevations from 1,600 to 3,000 feet.

A primary characteristic of high-quality coffees is how fast the coffee cherry (fruit) matures, with slower maturing coffee cherries generally producing a higher quality coffee bean (e.g., brighter acidity and nicer flavour).

Tasting Notes for Costa Rica La Lapa (SHB)

| Country | Costa Rica |

| Screen Size / Grade | SHB, SHG, SCR 18 |

| Bean Appearance (green) | Blue/Green |

| Acidity | Medium-high |

| Body | Medium-Light |

| Bag Size | 69kg |

| Harvest Period | November to February |

| Description | The La Lapa region in Costa Rica has rich volcanic soil which assists in producing this rich and delightful coffee. Note the prominent sweetness and balanced citric acidity with subtle nectarine notes. Great as espresso and filter. |

| Tasting Notes | Neutral and balanced, fruity, citrus notes |

| Strength | |

| Processing Method | Washed (Wet Processed) |

| Altitude | 900 – 1400 MASL |

History of Coffee in Costa Rica

Coffee production in the country began in 1779 in Meseta Central which had ideal soil and climate conditions for coffee plantations. Coffea arabica first imported to Europe through Arabia, whence it takes its name, was introduced to the country directly from Ethiopia. In the nineteenth century, the Costa Rican government strongly encouraged coffee production, and the industry fundamentally transformed a colonial regime and village economy built on direct extraction by a city-based elite towards organized production for export on a larger scale. The government offered farmers plots of land for anybody who wanted to harvest the plants. The coffee plantation system in the country, therefore, developed in the nineteenth century largely as a result of the government’s open policy, although the problem with coffee barons did play a role in internal differentiation and inequality in growth.

Soon coffee became a major source of revenue surpassing cacao, tobacco, and sugar production as early as 1829. Exports across the border to Panama were not interrupted when Costa Rica joined other Central American provinces in 1821 in a joint declaration of independence from Spain. In 1832, Costa Rica, at the time a state in the Federal Republic of Central America, began exporting coffee to Chile where it was re-bagged and shipped to England under the brand of “Café Chileno de Valparaíso”. In 1843, a shipment was sent directly to the United Kingdom by the Guernseyman William Le Lacheur, captain of the English ship, The Monarch, who had seen the potential of directly cooperating with the Costa Ricans. He sent several hundred-pound bags and following this the British developed an interest in the country. They invested heavily in the Costa Rican coffee industry, becoming the principal customer for exports until World War II. Growers and traders of the coffee industry transformed the Costa Rican economy and contributed to modernization in the country, which provided funding for young aspiring academics to study in Europe. The revenue generated by the coffee industry in Costa Rica funded the first railroad linking the country to the Atlantic Coast in 1890, the “Ferrocarril al Atlántico”. The National Theater itself in San José is a product of the first coffee farmers in the country.

Coffee was vital to the Costa Rican economy by the early to mid-20th Century. Leading coffee growers were prominent members of society. Due to the centrality of coffee in the economy, price fluctuations from changes to conditions in larger coffee producers, like Brazil, had major reverberations in Costa Rica. When the price of coffee on the global market dropped, it could greatly impact the Costa Rican economy.

In 1955 an export tax was placed on Costa Rican coffee. The current export tax is levied at 1.5%. In 1983, a major blight struck the coffee industry in the country, throwing the industry into a crisis that coincided with falling market prices; world coffee prices plummeted around 40% after the collapse of the world quota cartel system. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, coffee production had increased, from 158,000 tons in 1988 to 168,000 in 1992, but prices had fallen, from $316 million in 1988 to $266 million in 1992. In 1989, Costa Rica joined Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador to establish a Central American coffee retention plan which agreed that the product was to be sold in instalments to ensure market stability. There was an attempt by the International Coffee Organization in the 1990s to maintain export quotas that would support coffee prices worldwide.

At present, the production of coffee in the Great Metropolitan Area around the capital of San José has decreased in recent years due to the effects of urban sprawl. As the cities have expanded into the countryside, poor plantation owners have often been forced to sell up to building corporations.

Interested in some Costa?

Visit our Costa Rica page or Espresso Bar to buy a bag of our Costa Rica La Lapa (SHB).