Guatemala Antigua Acate (SHB)

About Guatemala and its Coffee Production

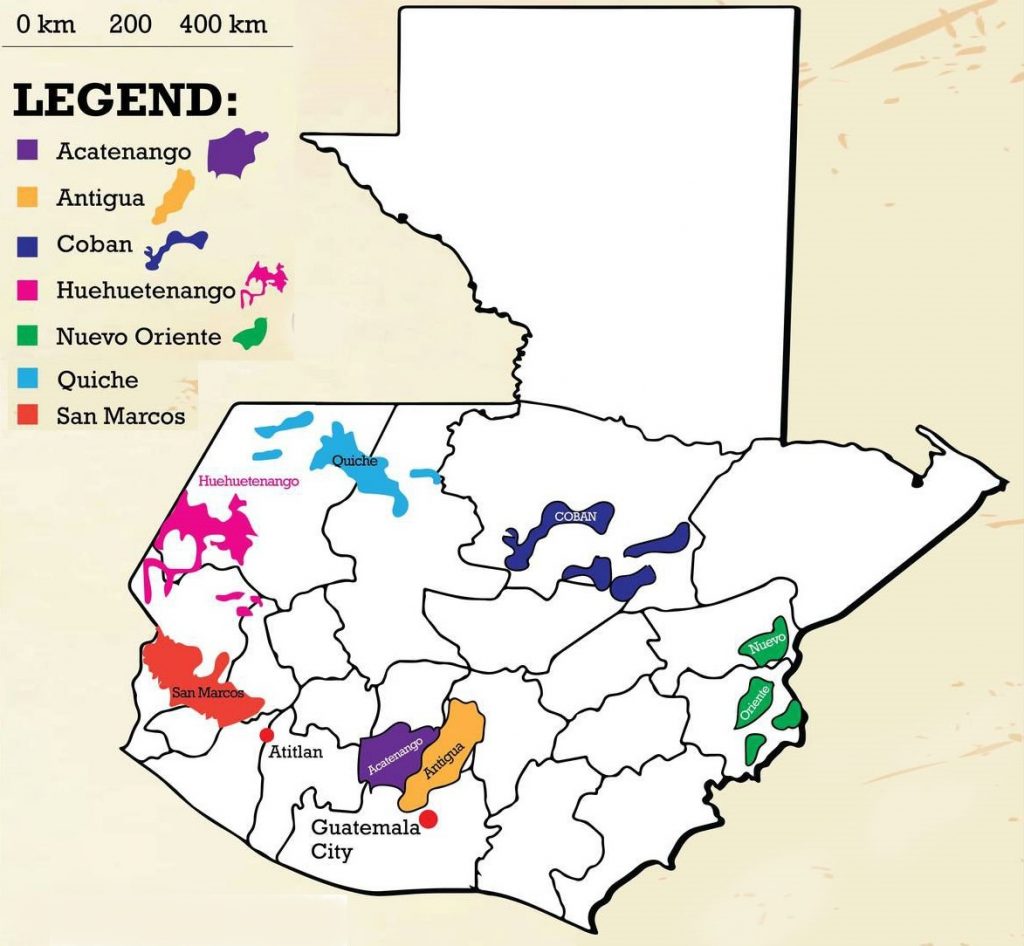

Guatemala boasts a variety of growing regions and conditions that produce spectacular coffees. Today, the country is revered as a producer of some of the most flavorful and nuanced cups worldwide.

Coffee production in Guatemala began to develop in the 1850s. Coffee is an important element of Guatemala’s economy. Guatemala was Central America’s top producer of coffee for most of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century, until being overtaken by Honduras in 2011, despite its small size, Guatemala is still one of the top ten coffee producers in the world with more than 204,000 metric tons of coffee beans a year.

The Guatemalan coffee sector is a behemoth. It generates around 40% of all agricultural export revenue and almost ¼ of the population is involved in producing the 3.6 million bags of coffee Guatemala exports each year.

Guatemala’s strictly hard beans (those grown above 1,350 meters above sea level) are considered to be among the world’s best coffee. In particular, beans grown on the southern slopes of the country’s many volcanoes are considered highly desirable.

Guatemala’s stellar coffee reputation is a combination of the right environmental conditions and a strong focus on cultivation and processing methods. Coffee is widely cultivated and grows in 20 of the 22 departments in Guatemala. High altitudes, consistent rainfall and mineral-rich soils make coffee an excellent crop across much of Guatemala. The nearly 300 unique microclimates mean that Guatemalan coffees boast a diverse range of flavours.

Almost all coffee is Arabica and 98% is shade-grown. Nearly all Arabica production is Fully washed, but natural and honey methods are becoming increasingly popular and producing many excellent lots. Many in the country are employing experimental processing methodologies, including soaking after washing, and Guatemalan farmers have been at the forefront of greenhouse drying methodologies. Guatemala’s high altitudes, diverse microclimates, consistent rainfall patterns, and excellent cultivation and processing, make for a variety of distinctive types of Guatemalan Arabica coffees.

The Guatemalan coffee industry experienced a major setback with the 2010 appearance of Coffee Leaf Rust (CLR) in Latin America. The epidemic peaked in severity in 2012, and though CLR continues to affect some farms, Guatemala continues to produce high-quality, record-breaking coffees. In 2017, new and varied processing methods pushed prices at the Guatemalan Cup of Excellence contest to record highs.

Smallholder farmers have been hit especially hard by coffee leaf rust (CLR). World Coffee Research (WCR) and Anacafé have worked together to introduce new CLR-resistant varieties—and the best ways to grow them—into smallholder communities.

Where does the Guatemala Antigua Acate (SHB) come from?

Guatemala Antigua Acate comes from the Antigua region of Guatemala from an estate called Acate, located in one of eight growing regions within Guatemala.

The soil in the Antigua region is rich in nutrients, from minerals deposited by Agua and Acatenango volcanoes in past eruptions. The active Fuego volcano leaves new mineral deposits to this day, keeping the soil fertile. Fertile soil, a large amount of rain, and consistent temperature in the region make great coffee the Antigua region is famous for.

Volcanic pumice in the soil retains moisture, which helps offset Antigua’s low rainfall. In Antigua, shade is incredibly dense to protect the coffee plants from the region’s occasional frost.

The rich volcanic soil and rainforest conditions produce a well-balanced Arabica coffee with a smooth finish.

The region produces some of the finest coffees in the country. The coffee is grown in the shade at 5,000 to 5,700 feet above sea level and collectively wet-milled and sun-dried by hand.

What is CLR (Coffee Leaf Rust)

Hemileia vastatrix is a basidiomycete fungus of the order Pucciniales (previously also known as Uredinales) that causes coffee leaf rust (CLR), a disease affecting the coffee plant. Coffee serves as the obligate host of coffee rust, that is, the rust must have access to and come into physical contact with coffee (Coffea sp.) in order to survive.

CLR is one of the most economically important diseases of coffee, worldwide. Previous epidemics have destroyed coffee production in entire countries. In more recent history, an epidemic in Central America in 2012 reduced the region’s coffee output by 16%.

The primary pathological mechanism of the fungus is a reduction in the plant’s ability to derive energy through photosynthesis by covering the leaves with fungus spores and/or cause leaves to drop from the plant. The reduction in photosynthetic ability (plant’s metabolism) results in a reduction in quantity and quality of flower and fruit production, which ultimately reduces the beverage quality.

At first, the spots are 2-3 mm diameter, expanding up to 15 mm diameter, and forming yellow-orange powdery blotches on the underside of leaves and yellow areas on top. Later, the centres of the spots on the top turn brown with yellow margins. Blotches may merge and cover the leaf blade. In severely affected plants, leaves fall and branches die back.

Spores are produced in the yellow-orange blotches on the undersurface of leaves. They are spread by wind but require water for germination. Insects also spread them. In countries where there is a dry season, the spores survive in infected leaves.

The disease is severe on arabica coffee, especially when grown in warm, moist areas in the lowlands (under 1500 m above sea level). The infection causes leaf fall, and this, in turn, affects the growth of new stems, which bear the next season’s crop.

Damage of a different kind occurs if there is a rust epidemic on trees with high yields. It is called “overbearing dieback”. Loss of leaves leads to the movement of food from the shoots and roots into the berries, which may ripen prematurely, resulting in beans of poor quality. Overbearing dieback may eventually kill the trees.

Plants weakened by rust are also more susceptible to attack by anthracnose (another fungus), which is not normally the cause of a serious disease. Overall, a 30 to 50% reduction in yield is possible from coffee rust.

Tasting Notes for Guatemala Antigua Acate (SHB)

| Country | Guatemala |

| Screen Size / Grade | Screen 16/18, SHB |

| Bean Appearance (green) | Rich green, high grade finish |

| Acidity | Medium |

| Body | Full |

| Bag Size | 69kg |

| Harvest Period | August – April |

| Description | This is a complex Antigua, produced in rich volcanic soils and with a near-perfect temperate climate. This microclimate produces a coffee with crisp sparkling acidity and full-body, with intense flavour characteristics. |

| Tasting Notes | Highly fragrant with flavours of bitter chocolate and spices. Elegant and refined with incredible complexity and balance. |

| Strength | |

| Processing Method | Fully Washed |

| Altitude | 1400 – 1600 MASL |

History of Coffee in Guatemala

The coffee industry began to develop in Guatemala in the 1850s and 1860s, initially mixing its cultivation with cochineal. German immigrants played “a very important role” in the introduction of coffee to the country, according to Marta Elena Casaús Arzú. Small plantations flourished in Amatitlán and Antigua areas in the southwest. Initial growth though was slow due to a lack of knowledge and technology. Many planters had to rely on loans and borrow from their families to finance their coffee estates (fincas) with coffee production in Guatemala increasingly owned by foreign companies who possessed the financial power to buy plantations and provide investment.

A scarcity of labourers was the main obstacle to a rapid increase in coffee production in Guatemala. In 1887, the production was over 22,000,000 kg (48,500,000 lb). In 1891, it was over 24,000,000 kg (52,000,000 lb). From 1879 to 1883, Guatemala exported 133,027,289 kg (293,274,971 lb) pounds of coffee. By 1902 the most important coffee plantations were found on the southern coast.

Many acres of land were suitable for this cultivation, and the varieties that were produced in the temperate regions were superior. Coffee was grown around Guatemala City, Chimaltenango, and Verapaz. The majority of the plantations were located in the departments of Guatemala, Amatitlan, Sacatepequez, Solola, Retalhuleu, Quezaltenango, San Marcos, and Alta Verapaz.

In June 1952, during the Guatemalan Revolution, Congress passed Decree 900, also known as the Agrarian Reform Law. The law redistributed land from nearly 1,700 estates to 500,000 landless peasants. The majority of beneficiaries were indigenous people who had not had access to land since the Spanish Conquest in the 1500s. In turn, the law angered many powerful landowners, including the United Fruit Company and the United States, who saw the reform as a communistic threat. The land reform law is often cited as an inciting factor in the 1954 coup d’état that marked the beginning of decades of civil war.

The Guatemalan civil war did not end until 1996, and the violence of the second half of the 20th century hindered the Guatemalan coffee industry significantly. Peacetime stability slowly worked to spread coffee production beyond historic coffee growing regions. Beginning in the 21st century, the land, where popular crops like macadamia and avocado were once grown, came to be replaced with coffee.

Interested in some Guatemala?

Visit our Guatemala page or Espresso Bar to buy a bag of our Guatemala Antigua Acate (SHB).